Lord Mountbatten was close to the royals, but his role was a complex one

In the first episode of the new series of The Crown, the Queen is lunching, en famille, at Buckingham Palace with Lord Mountbatten, played with taut charm by Charles Dance. As Prince Charles ducks out to visit Camilla Parker Bowles, the Queen asks of her son: “How is he, Dickie?”, adding: “He talks to you more than anyone.”

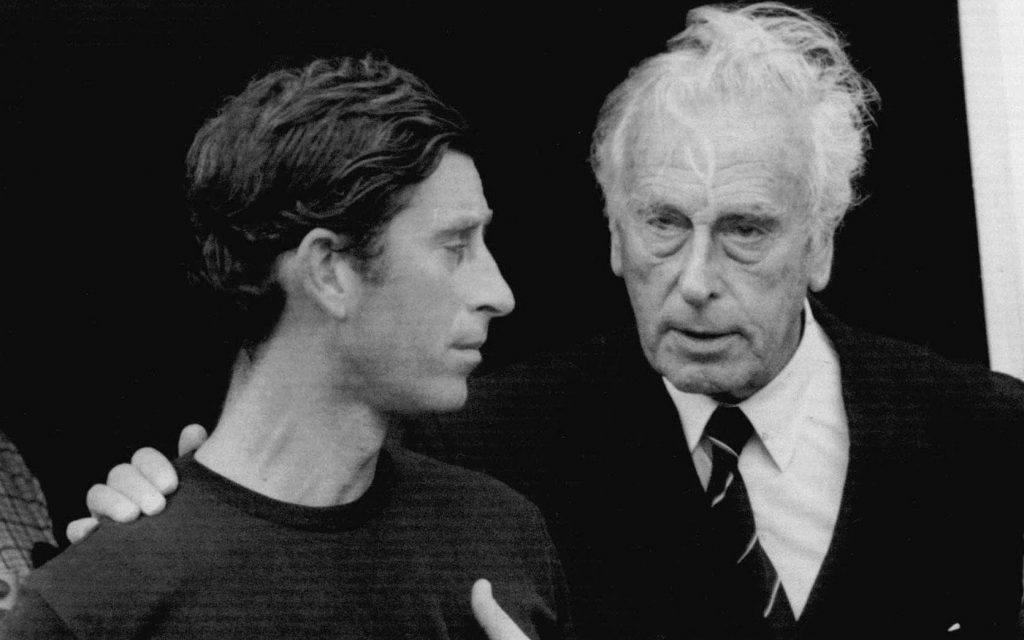

Netflix’s mega-budget series, whose highly anticipated fourth season is released today, establishes Charles’s “honorary grandfather” as pivotal to monarchical familial relations. But who was the real Mountbatten? In the same episode, Charles and Mountbatten row over the Prince’s relationship with Camilla. Mountbatten urges him to find “a bride with no past”. Prince Charles accuses his adored mentor figure of “playing for the other side.” Of being “a fifth columnist who makes a show of being a great ally.”

Mountbatten, for all his contacts and charisma, seems to have spent much of his life negotiating a tightrope between meddling, manipulating and mediating. This week saw the screening of a documentary entitled Lord Mountbatten: Hero or Villain? Charges include that he was a mendacious chancer, whose achievements in bringing forward Indian independence are hotly disputed. He was certainly a divisive figure.

Queen Victoria’s great-grandson, born in 1900 and Prince Philip’s uncle, the British Admiral of the Fleet, was tragically and brutally murdered by the IRA in Ireland in August 1979 alongside other family members. The Royal family were devastated and Charles, in particular, grieved the man who was his closest confidant. Mountbatten was a major influence behind Philip’s marriage to Queen Elizabeth, and instrumental in the Royal family taking the Mountbatten name.

But as writer Andrew Lownie asks in his book The Mountbattens: ‘Was [he] one of the outstanding leaders of his generation, or a man over-promoted because of his Royal birth, high level connections, film star looks and ruthless self promotion?’

When Mountbatten married the beautiful heiress Edwina Ashley in 1922, King George V, Queen Mary and most members of the Royal family attended, while Edward, then the Prince of Wales, was best man. It was a source of bitter regret to Edward that when he married Wallis Simpson in 1935, Dickie did not return the favour. Although the abdicated king wished that his brothers would be his best men, following Royal tradition, when the savage realisation hit that not one member of his family would attend his nuptials in France, he turned to his old friend, Dickie.

Mountbatten and Edward became close in 1919 when Dickie acted as his honorary ADC on a royal tour. According to Lownie: “It is not entirely fair to say that Mountbatten refused the prince, as initially Edward was very keen to have his brothers, but Mountbatten kept himself ready. When the Royal family told him that he could not go to the Windsors’ wedding as everyone was being banned, he soon realised which side his bread was buttered. His immediate loyalty was to the new king and queen.”

Naturally, this wounded Edward, who, in late age, forgave him. A perspicacious Wallis hadn’t warmed to Mountbatten, anyway, suspicious of his motives and turncoat behaviour.

“Mountbatten had a slightly unusual relationship with the Royal family,” explains Lownie. “He was the last godchild of Queen Victoria, friendly with George VI at Cambridge, was a slight mentor to the Queen when she came to power but he was not in direct line to the throne. Yet he was always writing himself into the script. He always thought that he was helping the Royal family and the courtiers. He had a strong sense of entitlement and saw himself as a fixer.”

This was unbecomingly evident after the death of the Duke of Windsor in 1972. At the Duke’s funeral, the Duchess of Windsor was seated between Prince Philip and Lord Mountbatten. “They both bent her ear about artefacts and archive material returning to the Royal collection,” says Lownie. “Some say that vans practically turned up the next day and people took things from the Windsors’ Parisian home. There is some confusion about various meetings that Mountbatten had with Wallis and whether things were taken with her permission or were just nicked.”

The Duchess of Windsor’s former secretary and trusted confidante, Johanna Schutz, gave me the original letter, never before published, which Mountbatten wrote to Wallis on February 19 1973, the year after the Duke’s death. The Duchess bequeathed this to her, alongside other private papers. Miss Schutz wanted me to have this clear example of Mountbatten’s machinations, she said, so I could “better understand what had gone on and how much the Duchess had to suffer again after HRH’s death.”

It was clearly agonising for Wallis, mired in grief, to have to endure Mountbatten’s attempts to reclaim the family silver. In the letter, sent from his family home, Broadlands, in Hampshire, addressed to “Wallis dear,” he writes: “My only idea has always been to be as helpful to you as possible in the sad circumstances of David’s death, but all the decisions rest solely with you. I know all David’s family feel the same way and want to be helpful without interfering.” Staggeringly, given their history, he continues; “Would it be any help my offering my services as one of the executors of your will? I was David’s devoted friend and he was my best man and I would like to do this for you if you would like it.” He signs off jauntily: “Please look after yourself and don’t go breaking any more bones. Much love from your old friend, Dickie.”

On Lord Mountbatten’s advice, the Duchess had already returned the Duke’s Garter robes, uniforms, orders and decorations to the Queen. “I had a huge box full of diamond insignias from the Emperor of India, which the Duchess gave back,” Miss Schutz told me. However, the repeated presence of Dickie in Wallis’s home, picking over precious objects d’art, insisting that they should be returned to the Royal family, unsurprisingly, put her back up.

“Mountbatten terrified the Duchess,” said Miss Schutz, “She was always so nervous before he came.” According to Mountbatten’s daughter, Lady Pamela Hicks, her father was adamant that some gold and silver kettle drums belonged back in London, not with the Duchess in Paris.

Lady Pamela told her daughter, India Hicks, in a podcast: “We had a real battle when the Duke of Windsor went into exile. He took as his private possessions one or two things – actually beautiful little boxes – that were his father’s or grandfather’s. My father thought he shouldn’t have taken those because they became state things. My father fought an endless battle to try to get Wallis to hand those back. He never succeeded because by that time she had descended into dementia, and she had that terrible lawyer who ruled her life.”

While it is true that Wallis’s life ended pitiably at the hands of Swiss lawyer, Maitre Blum, who controlled her affairs, and that she had lapses of senility, she was fully astute to Mountbatten’s acquisitive ways. Lady Gillian Tomkins, wife of the new British ambassador in Paris, Sir Edward Tomkins, told author Caroline Blackwood in 1995: “The behaviour of the Royal family was quite tactless at this point. They had snubbed the Duchess for years and then once the Duke had gone, they started making friendly overtures toward her because they wanted her jewels and possessions. The Duchess was much too clever not to see through that. She always hid the Royal swords before Mountbatten visited her.”

In The Crown, Prince Charles and the royal family forgive Mountbatten his self-aggrandising meddling. Wallis was, through bitter experience, more discerning.