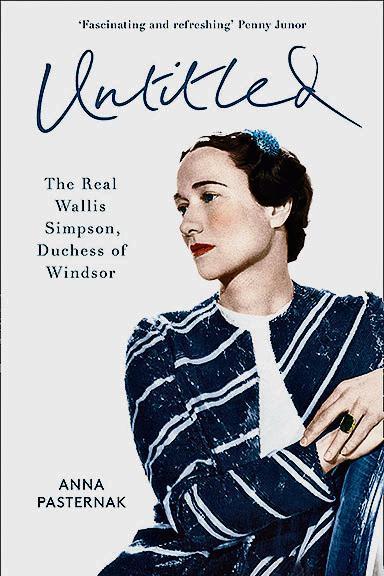

MICHAEL OCHS ARCHIVES/GETTY IMAGES

A new biography paints Edward VIII’s wife as a tragic figure unfairly vilified by the royal family, says Ysenda Maxtone Graham

Even if the EU has 40 words for “no”, the British royal family surely put Michel Barnier in the shade. When it comes to flinty-hearted negotiators refusing to soften their stance towards someone they consider to be beyond the pale, you can’t beat the royals in the mid-20th century. For 35 years they responded in the negative to the Duke of Windsor’s repeated requests that his wife should be granted the title “Her Royal Highness”.

So the apposite title of this biography of Wallis Simpson is Untitled. It’s a rehabilitation job on the woman for whom Edward VIII abdicated the throne in 1936; he would rather marry a divorcée and cause a constitutional crisis than be king. Anna Pasternak tells us in the acknowledgments that she asked Simpson’s previous biographer, Anne Sebba (That Woman, 2011), to sum up her views on Simpson. Sebba’s response was: “What’s to like?” To which Pasternak replied that her view was exactly opposite: “What’s not to like?”

How Simpson’s enemies — her mother-in-law, Queen Mary, and her sister-in-law Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother — would have shuddered, not only at this opinion, but also at the modern jargon. Pasternak’s mission is to make us love Simpson, to see her as a tragic heroine, unfairly vilified, who did all she could to make the man who loved her desist from giving up the crown to marry her.

The book does have the Desert Island Discs effect of making you take notice of and see the compassionate, vulnerable sides of someone you’ve subconsciously compartmentalised all your life as too rich, too thin and, let’s be frank,

too American. (During her one stay there, in 1936, Simpson introduced the triple-decker sandwich to Balmoral.)

As with most royal biographies, there’s little here that hasn’t been written somewhere before. Pasternak quotes extensively from Edward’s memoir A King’s Story and Simpson’s Mills & Boony autobiography The Heart Has its Reasons (“I was prepared to go through rivers of woe, seas of despair, and oceans of agony for him”), as well as from Sebba, and from James Pope-Hennessy’s biography of Queen Mary and Philip Ziegler’s Edward VIII. Pasternak whizzes us through Simpson’s 1890s Baltimore childhood in three pages, her disastrous eight-year first marriage to an alcoholic in a page and a half, and her final widowed, miserable, lonely, gaga 14 years (from Edward’s death in 1972 to her death at the age of 89 in 1986) in another three pages.

So why read it? Well, Pasternak did interview a few fresh people, including John Julius Norwich, whose parents, Duff and Diana Cooper, knew the Windsors well in Paris, Count Rudi von Schönburg, who ran the Marbella Club in the 1960s, Anne Pleydell-Bouverie, whose parents knew them in the Bahamas, and a duke called David Maude-Roxby-Montalto di Fragnito, who met Simpson a few times on Palm Beach.

These people bring fresh observations to bear, such as (from Norwich): “Papa could see that this thing had got far too big for Wallis and she was longing to get the hell out… but the King was determined to marry her.” Or (from Von Schönburg) “The Duke harboured this terrible fear that ‘they didn’t treat Wallis well when I was alive, how will they treat her when I am dead?’ ”

What makes the book unputdownable is Pasternak’s lively and detailed (and thankfully not Mills & Boonsy) retelling of this ever-fascinating, ridiculously poignant love story. The happily married Simpsons met Edward in 1932 through their friend Thelma Furness, and they invited him to dinner at their mansion flat in

Bryanston Court in London. Edward invited them back for a weekend at his house, Fort Belvedere, in Surrey.

GETTY IMAGES

“She is a nice, quiet, well-bred mouse of a woman, with large startled eyes and a huge mole,” the MP Chips Channon wrote of Simpson in his diary. But there was something about her forthrightness that enchanted the Prince. There’s no factual back-up for the rumour that she hooked him with “sophisticated sexual practices” she had picked up in “singing houses” in China, where she spent a year in the 1920s after escaping from her first marriage. That was just prurient tittle-tattle that spread when the scandal broke. “Everything was a bid to discredit her,” said Norwich, “but she was the furthest thing from kinky.”

Although Simpson is the central character, this is as much a biography of Edward: just as nothing could separate them in life, no biographer can separate them in death. On every page you wince as they once more step towards a life of exiled futility.

Norwich said that his father was the only person who dared to warn Edward of the inevitable outcome, “that the whole blame for the catastrophe [of the Abdication] would be placed on Wallis, now and in history”. Edward did not heed this warning. There is no doubt that the tragic flaw that drives the story was his obsessive determination to have his own way, at all costs, in matters of love. This trait was revealed last year in Rachel Trethewey’s Before Wallis, which portrayed him as obsessive in his pursuit of his girlfriend of the moment. With Simpson, this obsessiveness reached the level of total dependency and blindness to all reason.

“Yes, but…” I kept wanting to say to Pasternak, who impresses on us that Simpson implored the prince to let her go, so she could return to her sweet, gracious, noble husband, Ernest. “I feel I am better with him than with you,” she wrote to Edward from the dismal rented house in Felixstowe in Suffolk where she was staying just before her divorce trial in Ipswich, “and so you must understand.”

She offered to return all the gifts Edward had given her, as well as the “life-changing sum of money” he had bestowed on her — although she was enchanted

by the royal lifestyle, she was emphatically not (Pasternak claims) a gold-digger. On crackly telephone lines, as she went into hiding in France in December 1936 when the news of the affair broke in the British press, she was overheard shouting at him: “Never leave your country. You cannot give in. You were born to this. It is your heritage.”

Edward took no notice, but she could just have not married him, couldn’t she? Or perhaps not. You just try having Edward VIII in love with you and see if you can escape. He simply went ahead and abdicated.

The story is made odder and sadder when you consider that Simpson never menstruated, so could never have children (a source of infinite sadness to her), and that (as Lady Cynthia Gladwyn explained to Hugo Vickers, who told it to Pasternak), “the prince had sexual problems. He was unable to perform.”

Here are some of Simpson’s traits that Pasternak mentions to build up a positive image. She was a wonderfully attentive hostess: if there was a legendary bore at the dinner table, she was the one who took the trouble to talk to them. She was a calming influence on the impossibly demanding Edward, whose bitterness towards his family (who persistently refused to meet his wife) increasingly infected his life. Each morning of their married life she wrote a “programme” for him and put it on the hall table, to help him to get through the long, pointless day ahead.

She loved her dear American aunt Bessie. She wrote affectionate letters to friends. She loved Ernest (but she did divorce him). It’s not true that she flew from the Bahamas to Miami every week during the war to have her hair done, but she and Edward did like shopping in Washington DC occasionally, taking 73 pieces of luggage.

Wise Ernest, who understood and cherished her, gently told her the truth about how inextricably bound up she was with Edward. “Would your life ever have been the same if you had broken it off? I mean, could you have settled down in the old

life and forgotten the fairyland through which you had passed? My child, I do not think so.”

Among the book’s excellent photographs, some published for the first time, there’s a hauntingly sad one of Simpson looking out of a window of Buckingham Palace watching the Trooping the Colour, utterly desolate, before Edward’s funeral in 1972. On that day, at last, she was invited to ride along The Mall with the Queen Mother in an open-topped carriage, but she declined. That gesture of friendship and reconciliation, one that would have brought so much happiness to Edward, had come too late.